Around eighty years after my paternal grandparents and aunt became Holocaust refugees, I began reflecting on this part of my family’s past. In the midst of that, I applied for the Memorial Gestures Residency at the Holocaust Centre North.

Weeks before the application I found a stack of envelopes sent between my grandparents when they were forced to be apart during the war. Folded into every few letters was a four-leaf clover. I read these tiny, dried and pressed plants as vessels that had carried love, hope and confidence in the future. Today, they seemed just as, if not more, powerful, having the ability to crush distances created by unspoken pain, buried deeper still by death and time.

In my application I wrote how I saw that stories could reflect fact, create meaning, hold a centre and provide us with what we need at a given moment. Some stories, I wrote, harden over time, or get tidied up. They may lose bits, facets or complexities, sometimes big chunks get hidden or stored away out of sight, but moreover what we need from them is likely to change. This, or elements of this, was true for me when receiving my family’s stories – so much was silenced. The clovers played an active role in revealing that which had previously gone unseen or unspoken. They were like tiny wands motioning at the past – waving in order to release, open, awaken or transform.

The residency began, and among the compiled resources the residency offered, was a talk by memory studies scholar Michael Rothberg in which he speaks about his book Multidirectional Memory. Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. One part of the talk stood out to me. Rothberg describes his ideas about a French documentary film, or rather a moment in the film Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer), in which cast member, Marceline, gives an account of her time in Auschwitz.

Rothberg speaks about having been drawn to the film because of its release date, 1961: the same year as the Eichmann trial, a pivotal moment in the construction of how the Holocaust is predominantly represented and remembered today, and also, the year before the end of the Algerian War of Independence against France.

I watched Chronicle of a Summer. It features Parisian students, workers, immigrants and the filmmakers themselves having conversations about how they live and if they are happy, they branch out broadly and loosely from their core questions to topics like human connection, work, prejudice, racism and colonialism.

Marceline’s testimony arrives around midway, as if folded into or tucked inside the film. The sequence feels separate from the rest of the documentary as the only moment belonging to a single person, not a couple or group. Marceline speaks, seemingly to herself, but more likely to or for the viewer. The sequence feels like a pocket within the film made of different material, distinct but dependent on the rest and hidden within its structure. It allowed me to slip inside, or maybe it released what had been held in. The unspoken, or unseen, finds a way out, and things, once again, felt like they were being revealed.

For Rothberg, Marceline’s testimony demonstrates the possibility of multidirectional memory, the idea that memories can be intertwined or layered in order to speak of or shed light onto other moments. The testimony, for example, set within the film, layers experiences of the Holocaust with those of the Algerian War and more broadly of racism and colonialism. Marceline’s story can be read as an allegory of public violence, and in particular the violence that took place during the Algerian War. This interpretation is all the more important given the censorship enforced in France in 1961 around the Algerian War: tools like allegory were the only way to speak of what was happening. The testimony was a breaking of various silences. Film critic Richard Brody speaks of these in his 2013 article about the film: “Silence, whether due to the official censorship regarding the war in Algeria or the social censorship of the experience of the Holocaust, comes off as a prolongation and repetition of trauma, a primary obstacle to self-realisation and self-fulfilment”.

As I watched Marceline’s testimony, something about the way it’s introduced, that which immediately precedes it, reminded me of how I had experienced the clovers. They too had broken a form of silence. I had imagined them as coming from a different reality, from the realm of magic, where things have the power to break the spells that bind people to silence or hold them captive in towers, far from loved ones. The testimony surfaces in the midst of a discussion on racism and colonialism, as one of the filmmakers points out the numbers tattooed on Marceline’s arm. She responds: “I was sent to a concentration camp because I am Jewish, this number was done to me in that camp. Do you know what that is, a concentration camp? “Yes, I saw a film about concentration camps, Night and Fog”. A man answers, as he does, we see a close-up of Marcelines hands.

She holds the stem of a light-coloured rose in her left hand. In her right hand, her index and middle finger hold a cigarette. Her thumb, ring and little finger caress the rose. She strokes it, starting at the base of the petals and following them up before pinching the flower slightly shut towards the top of the petals, as if to close the flower back up. She does this twice before the film cuts to Marceline walking holding her jacket closed against the wind and she begins her story.

Marceline’s rose acts like a genie’s bottle, as she touches it something held within is released. Her past as a Holocaust survivor had been alluded to in a previous conversation between Marceline, Marceline’s ex-boyfriend and one of the filmmakers, but it had gone unaddressed, maybe even suppressed. Marceline’s ex talks about his dissatisfaction with life. Marceline looks uncomfortable and says that she feels responsible for his sadness, because she took him out of his world and exposed him to things he might not have otherwise known. She desperately wanted their relationship not to fail. She wished for his youth to be different to hers. She thought she could make him happy in spite of it all, she loved him and still does. As she says ‘happy’ the camera moves down to her tattooed arm, and silence follows. The rose, a few scenes after, enables a breaking of that silence. It allows her story to emerge.

I came to the archives at Holocaust Centre North searching for clovers and roses, for moments of connection. I came looking for, and perhaps hoping to create, instances of magical release from spells of silence. In the archives, I was introduced to the stories and collections of Edith and Emil Culman.

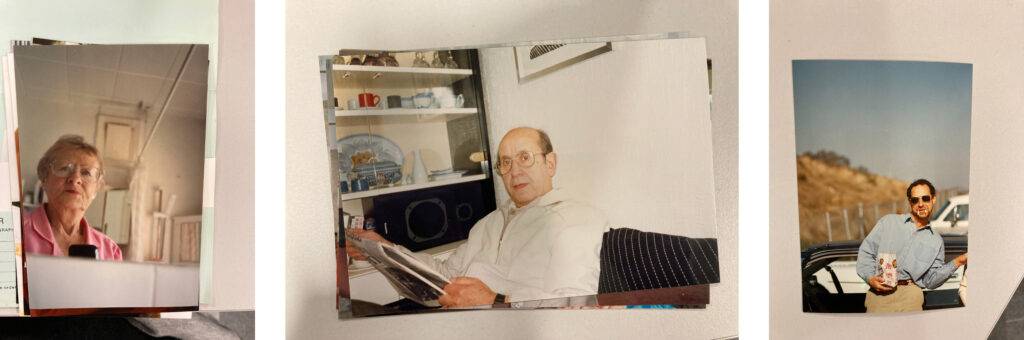

Edith was a Holocaust refugee from Germany who arrived in the UK in 1939. Emil was a Dachau Survivor from Poland who also arrived in 1939 only to be held in two internment camps, one in Surrey and another in Liverpool, before being deported to the Hay internment camp in Australia. He was released and returned to the UK late 1941. Edith and Emil met in St Albans and married not far from there in December 1942. They had one son, Emanuel who was born in 1945. They moved to Leeds in 1954.

Their collection is multifaceted. It holds the traces of what I have started to imagine as two tenaciously hopeful people. I started to tell myself stories of their unwavering commitment to one another, but more over to themselves. I found cards they exchanged on special occasions and boxes full of moments they captured in photographs, affectionately, artistically, candidly and experimentally.

Edith drew and her sketches had me imagining her sitting in the landscapes I held. I followed her to language and art history classes. I read letters she wrote to artists she admired, and their answers, that they had no time to meet her in person. I found Emils letter to the British Embassy in Warsaw as he searched for his parents and sister and the reply that gave him no answer. I found fiction Emil wrote in evening classes over many years, in some he looked back on what he had experienced in his earlier life. Through all this and more I saw them chipping away at walls of isolation to build bridges with the rubble they gleaned.

The collection held another important story too, that of their son Emanuel, born in 1945, who emigrated to the USA in the 1970’s. Emanuel wrote his parents countless, long typewritten letters, with details of his life, his hopes and dreams and struggles. After travelling across the USA, he settled in LA, the city of dreams, where he wrote stories, plays and screenplays for many years before moving to North Dakota and restoring a local movie theatre in a small town called Beach.

Courtesy of the Culman family.