Unpicking: The Gannex & I

“Unpicking” is currently available to view at Memorial Gestures, presented at Sunny Bank Mills. This exhibition runs until Saturday June 28th. More information available here: Artistic Responses to Collections · Holocaust Centre North

I grew up knowing my grandparents were Holocaust survivors, but it is only in the past few years that I’ve reflected on what this means to me. My grandmother’s death in 2019 was the catalyst for this reflection. Overnight, our family shifted from four to three generations and I no longer had a direct living connection to the Holocaust. Alongside natural feelings of grief came more unsettling feelings. Growing up aware of the horrors that came before me had resulted in a deep sense of anxiety. My grandmother, a German Kindertransport survivor, was triggered by our childhood misdemeanours. She would remind us how fortunate we were to have family when hers had perished. I knew that my Polish grandfather witnessed unimaginable horrors in the Radom Ghetto and Nazi concentration camps. I was only ten years old when he died and never heard him talk about his experiences, but nor did my mother who could only recall him joking about his “wartime medals.” My grandfather felt burdened with guilt at being the only member of his birth town to survive and he suffered from vivid nightmares. I only know this from the three-page testimony he wrote before his death.

Since embarking upon GCSE Art many years ago, I felt compelled to explore the Holocaust. But it’s taken many years to place myself within this subject, and to feel that this was ok. After all, I hadn’t experienced the Holocaust so why should I feel affected? With my grandmother’s passing came the recognition of how little I knew about my ancestry. Our family rarely discussed our history, but snippets would emerge during tense discussions around the Shabbat dinner table.

From 2022 to 2024, I embarked upon a period of research, exploring documents received through the Wiener Holocaust Library’s ITS service and World Jewish Relief. I listened to my grandmother’s Oral History testimony, recorded through AJR Refugee Voices, and I explored letters, telegrams, and photographs sent by my great grandparents before their deportation to Riga. In response, I created work in a laborious manner—printing, deconstructing, and reconstructing. This process helped me feel more in control of my ancestry and I began recognising where my anxieties originated. I could see that my work was centred less on legacy making and more about me.

1939-64 (close up), 2022

Martin Livesey.

During this research period, I discovered the Holocaust Centre North’s “Memorial Gestures” residency programme for contemporary artists, writers, and translators. I admired its embracing of nuanced conversations surrounding the Holocaust and its positioning within contemporary discourse. Motivated to learn from other families’ experiences, I applied for the residency and was delighted to be accepted. I was drawn to the Holocaust Centre North’s location in West Yorkshire, an area historically rooted in textile production. Post World War Two, many mills employed refugees, migrants, and European Voluntary Workers. This included Holocaust survivors and South Asian migrants who’d witnessed the Partition between India and Pakistan in 1947. With my grandfather rebuilding his life as a tailor and as textile practitioner myself, these interwoven histories felt poignant. On Holocaust Memorial Day, Holocaust Centre North Director Dr Alessandro Bucci said that “Those who live with trauma do not come to our work empty-handed. They bring with them ghosts—not always visible, but always present. To do this work is to make space for what cannot always be named.” I thought of those working together within the textile industry, navigating new lives whilst carrying their scars.

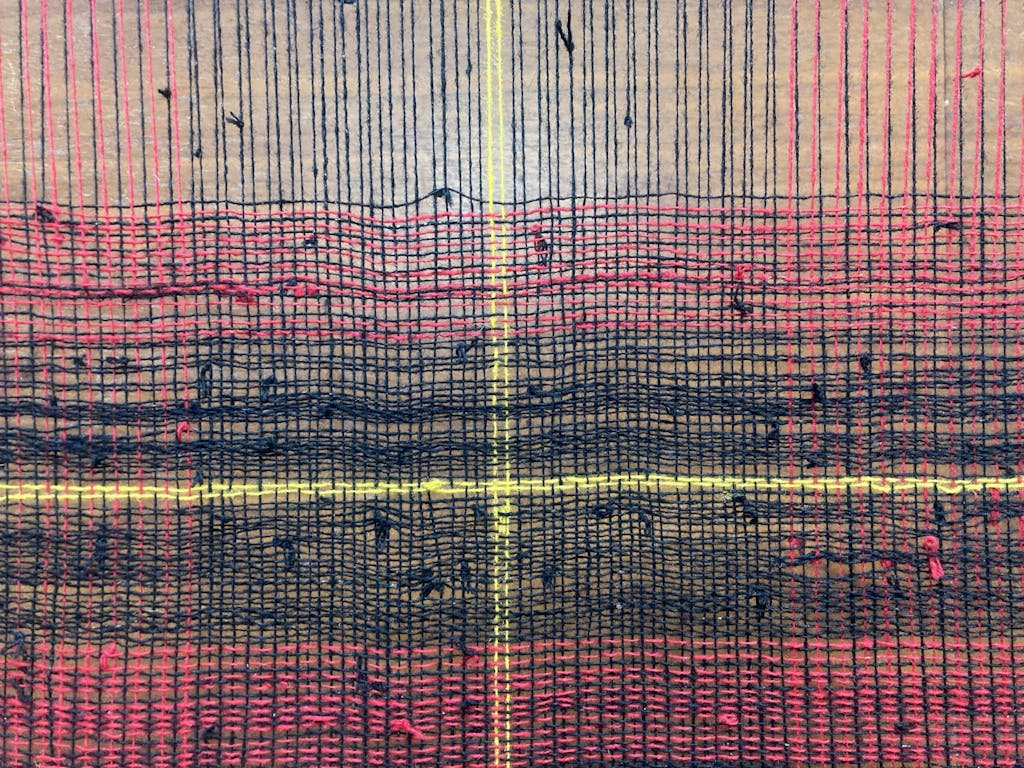

Within the Holocaust Centre North Archive, Margaret Kagan’s story resonated. After surviving by hiding in Kaunas Ghetto, Margaret and her husband Joseph came to Huddersfield. By 1951, Joseph had invented Gannex fabric, and their business Kagan Textiles Ltd started to flourish. Keen to explore this resilient, waterproof, warm fabric, I sourced two vintage Gannex coats. I posed, showing off the iconic lining and was struck by an image within the Holocaust Centre North Archive of the Kagan’s niece, Pauline Gardner, posing similarly. Pauline is the daughter of Holocaust survivors Val and Ibi Ginsburg who also worked for Kagan Textiles Ltd.

(Right) Laura Nathan modelling a Gannex coat, 2024, Martin Livesey.

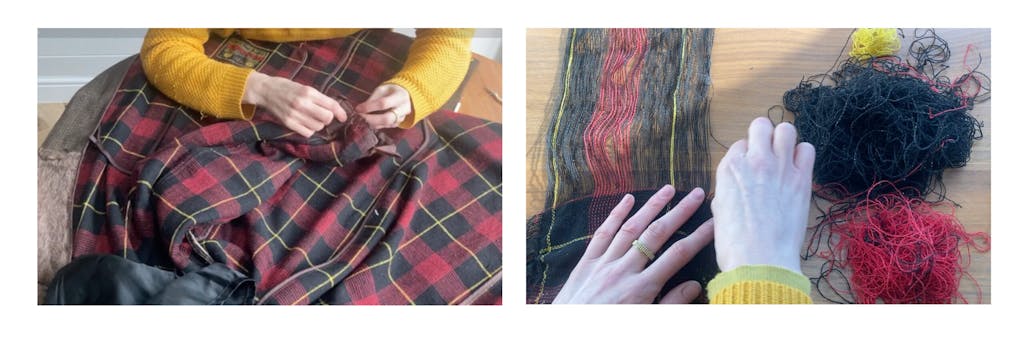

I started to unpick one of the coats whilst listening to survivor and multigenerational interviews. The survivors all connected to textiles – whether as an employee of Kagan Textiles Ltd, Yorkshire Mill workers, sewing machine engineers, or knitwear practitioners. Unpicking whilst listening forged a tangible link between the unwinding garment in my hands and the stories unfolding in my ears.

Discovering that Holocaust Centre North’s neighbour Heritage Quay (the University of Huddersfield’s Archive) housed “The White Line – Here, There, Then, Now Oral History Project” was pivotal. I listened to interviews with people who’d experienced the Partition between India and Pakistan before migrating to Huddersfield. To maintain the connecting thread, I focused on those who worked in textile mills. Parallels emerged between those who witnessed Partition and those who survived the Holocaust. Alongside trauma, displacement, loss, and anxiety, silence stood out. Sajida Ismail spoke of her mother’s experiences, sharing that “you hold onto your memory because it’s so traumatic you don’t want to share it…there are some things you just want to forget.” Val Ginsburg paralleled this, stating “It was just too horrific and upsetting to start reliving your past, so we kept quiet—a long silence.”

Returning to the Holocaust Centre North interviews, I was fascinated by a need for busyness. Survivor Iby Knill expressed how she had never been bored in her life. Her son Chris Knill recognised this need to “find ways of escaping from that continual reminder…. keeping going forward into something to keep yourself afloat.” Hannah Goldstone, granddaughter of survivor Martin Wertheim recognised her family’s difficulty to “sit down and just be.” She felt her grandfather never processed his feelings, recognising that “the minute you sit down you stop, (and) you then think about things that you don’t always want to think about.” I reflected on my own family’s busyness —the ease I feel when engaging in lengthy hands-on processes, and the anxiety I feel when not being “constructive.”

I continued unpicking the Gannex coat, recognising how symbolic the growing piles of threads were becoming and my compulsion to delve deeper. I found myself interrogating the Kagans with the same meticulousness I had with my ancestry. My initial fascination with the Kagans grew from the stark contrast between their family and mine. They were outspoken, bold risk-takers, which defied my understanding of blending in to keep safe. This fascination gradually evolved into a more complex one, as alongside uncovering the dirt trapped within the seams of the Gannex coat, I’d unearthed a more unsettling side to Joseph Kagan. This centred around Joseph’s ten-month imprisonment for fraud and tax evasion, the annulment of his knighthood, and scrutiny surrounding his personal and professional life.

Joseph Kagan had been the focus of the British Tabloids, Private Eye Magazines, and featured in the current affairs television show “World In Action”. However, it was the far-right papers and magazines — “Britain First,” “National Front News” and “Spearhead” who really revelled. Joseph was referred to as an alien immigrant millionaire with “contempt for the society that accepted him”, which highlights the agenda within these fascist papers. I initially felt deflated by the online discoveries which sat outside the acceptable narrative surrounding memorialisation. However, when listening to Margaret Kagan and daughter Jenny Kagan’s interviews, they openly discussed this counter narrative and Joseph’s relationship with the media, and a weight lifted. With silence being such a key commentary within my work, their openness was unearthing yet refreshing. It forced me to reflect upon the anxiety I feel surrounding saying or doing “the wrong thing” and where this stems from. Jenny Kagan described her father as a creative thinker with a “unique way of looking at things and seeing solutions that other people didn’t see” but she also acknowledged he was challenging due to his “lack of modesty, lack of humility, lack of willingness to behave.” She also recognised that despite her father’s aim “to be accepted by British society… (he) felt he’d always been seen as a jumped-up émigré.”

As my listening and unpicking came to an end, I felt compelled to piece together a selection of unpicked threads and recreate the iconic Gannex tartan lining, honouring those who successfully rebuilt their lives one delicate thread at a time, and as a nod to descendants who too carry the weight of their history. Above all, I wanted to celebrate the flaws, the vulnerability, and the resilience which makes us human. When Julia Kinch described her grandmother Iby Knill she stated, “You’re not just all of the good things and you’re not just all of the bad things. You are a perfect mix of all of them together in a way that is genuine.” Despite the fragile threads snapping, the knots causing obstructions and my frustrations rising; I persevered, rebuilding a delicate evocative piece of fabric — the threads saturated with history but forming a new identity of their own.

For the Memorial Gestures exhibition, I created an installation entitled “Unpicking: The Gannex & I” which highlights my journey of unpicking, learning, and rebuilding. Learning from others has developed a sensitivity to how I approach my own family’s narrative, and I’ll be mulling over things for a long time to come. I’m hugely grateful to the Team at Heritage Quay and at Holocaust Centre North, notably Paula Kolar, Curator of Contemporary Practices, and Jenny Kagan, Chair of The Holocaust Survivors’ Friendship Association and Holocaust Centre North. Their support has enabled me to push through the unsettling, delve deeper, and step out of my comfort zone.