Hello, I’m Laura Fisher! I am honored to have been chosen to create artistic responses to the archive at Holocaust Centre North through the Memorial Gestures artist’s residency, and I’m excited to introduce myself to you today.

I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A., and lived in Chicago for a number of years before moving to Paris, France. I hold a BFA in Photography from the University of Cincinnati and an MFA in Drawing from Paris College of Art, and I currently teach drawing at the American University of Paris. As the international artist-in-residence at Holocaust Centre North, I will continue living and working in France, while making occasional trips up to England to conduct research.

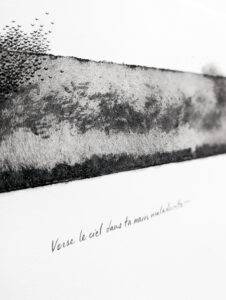

Grounded in the principle of Standpoint Theory, my work explores the narratives of oppressed parties from the point of view of the people who lived them. Incorporating textiles, drawing, printmaking, and writing, I use interdisciplinary methods to create a dialogue between past and present, weaving together the threads of lesser told stories in order to reposition history toward a more personal, human-centered context. Reflecting on concepts such as displacement, identity, memory, and questioning the notion of ‘home’, my work simultaneously serves as a visual conversation, a call to community, and a tribute to the grief inherent in traumatic histories.

A lot of folks are surprised when I tell them I applied to this residency not because of a specific interest in the Holocaust, but for the opportunity to work with traumatic histories and challenge conventional methods surrounding them. I wanted to explore better ways to tell these stories, while treating them with complexity and care. Back in September, a friend of mine from grad school first told me about Memorial Gestures and encouraged me to apply—she had seen my MFA degree project in which I interviewed women about their stories of migration, and thought I would be perfect for this type of work. I was not familiar with Holocaust Centre North, but was immediately intrigued upon hearing about the residency and learning more about the Centre. Memorial Gestures seemed, to me, incredibly unique in both its nature and philosophy. This residency would allow me the opportunity to work with materials that I would not have access to otherwise, of course, but it was also the only archive-based residency I had found that actively encourages residents to challenge preconceived notions about how difficult histories are treated, and how we can rethink traditional curatorial practices. The nature of the residency felt intimate and empathy-driven, and very much aligned with my personality, my beliefs, my sensibility, and my art.

During my first in-person visit to Holocaust Centre North in December, I was initially overwhelmed by the scope of the permanent exhibition and the amount of materials in the archive. The scale of the tragedy felt incomprehensible—I remember sitting in the bedroom of my Airbnb, a pit in my stomach, feeling like nothing I could do would possibly be enough. My head swirled with questions and worries. How could I, or anyone, create anything encompassing the depth of despair, of the pain that this hatred and genocide caused? In what ways could I show respect to the people who entrusted their lives and the lives of their families to the collection? How could I foster a culture of care, how could I create art that would make those affected by this tragedy feel seen, cared about, witnessed? How do I touch this?

I don’t profess to have the answers to all these questions (and, to a certain extent, I believe several of these questions are unanswerable). But I felt a breakthrough when I shifted toward a more individual, person-centered approach in my research and production: focusing on stories that I felt a connection to, that seemed relatively underrepresented or lesser-told within the collection, or that sparked something in me artistically. To learn about and convey one person’s life through an intimate lens, in the hopes that I can help others understand the depths of ‘What Was Lost’ during the Holocaust—what was stolen from these families whose lives were irrevocably changed.

While exploring the archive at Holocaust Centre North, I noticed that textiles seemed to be a common thread (pardon the pun!) running through many of the survivors’ lives, whether it was through work in factories after relocation (Ibi and Val Ginsburg), knitwear production (Iby Knill), textile manufacturing (Margaret and Joseph Kagan), textile art (Edith Culman), or crocheted handiwork (Tom Kubie’s mother). Political conditions in the UK likely played a role in textiles being a part of many Jewish immigrants’ lives; as survivor Val Ginsburg explains in an interview recorded by Holocaust Centre North, Holocaust refugees were allowed to work in one of two industries upon arrival in England: textiles, or coal mines. (Women, alternatively, could apply to work in domestic service.) Val, as it turns out, chose the former—even though Jewish immigrants were given a lower pay rate. Given the myriad forms textiles have taken throughout many survivors’ lives (as well as the storied significance of textiles to Jewish cultural history), it seemed fitting to work with textiles not only as a research focus, but also as a material and conceptual basis for the artwork I produce throughout this residency.

Besides Val and Ibi Ginsburg, I’ve been quite steeped in the lives of Iby Knill, Tom Kubie, Edith Goldberg, and Saul Erner. Additionally, I have been reading Dara Horn’s book People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present (and listening to her excellent podcast Adventures with Dead Jews), Bernice Eisenstein’s memoir I Was the Child of Holocaust Survivors, and Iby Knill’s two autobiographies: The Woman Without a Number and The Woman with Nine Lives. And since stumbling upon Michael Marrus and Robert O. Paxton’s seminal Vichy France and the Jews in a used bookstore in the Latin Quarter, I have been immersed in learning more about local Holocaust history here in Paris and throughout France at large.

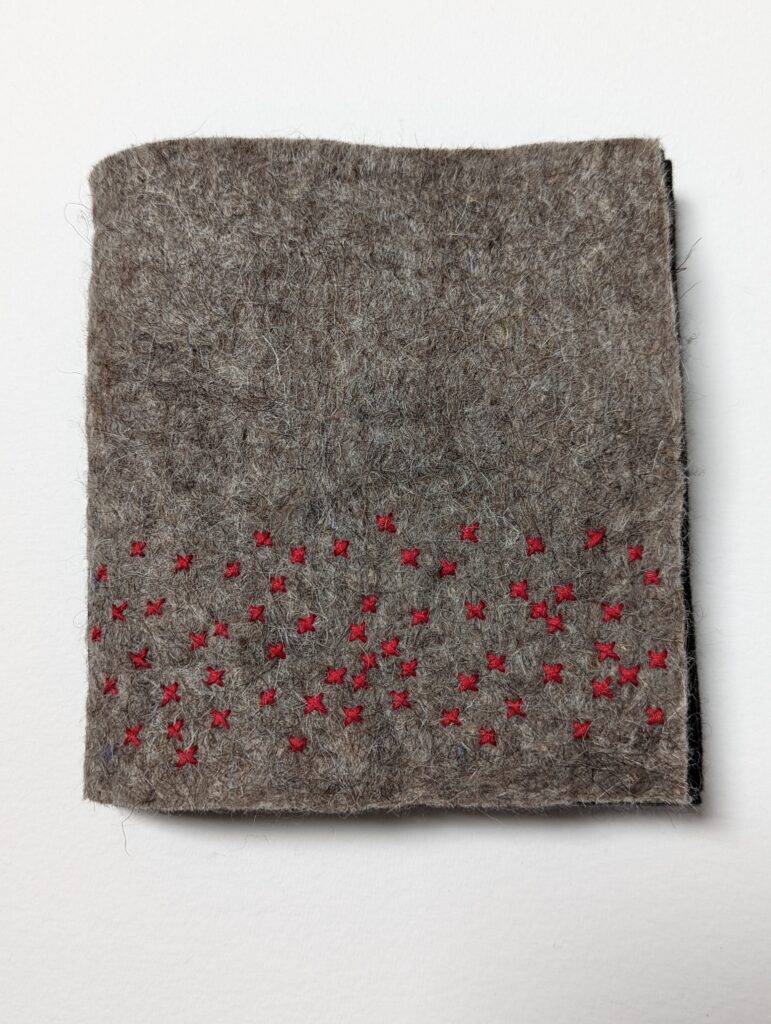

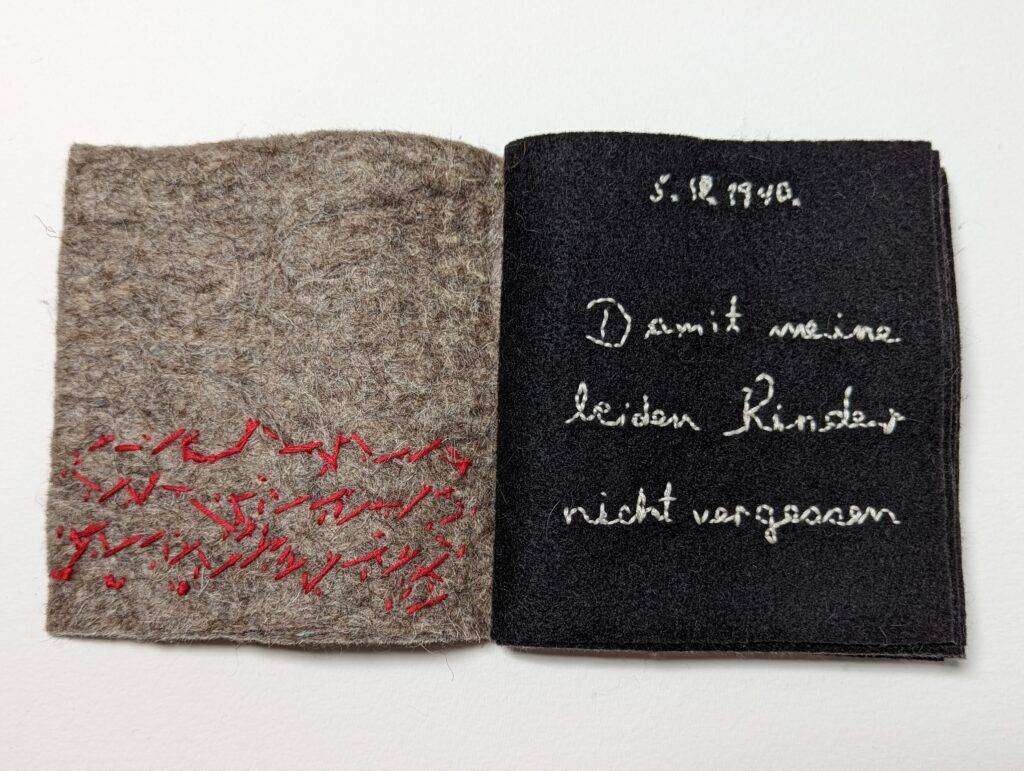

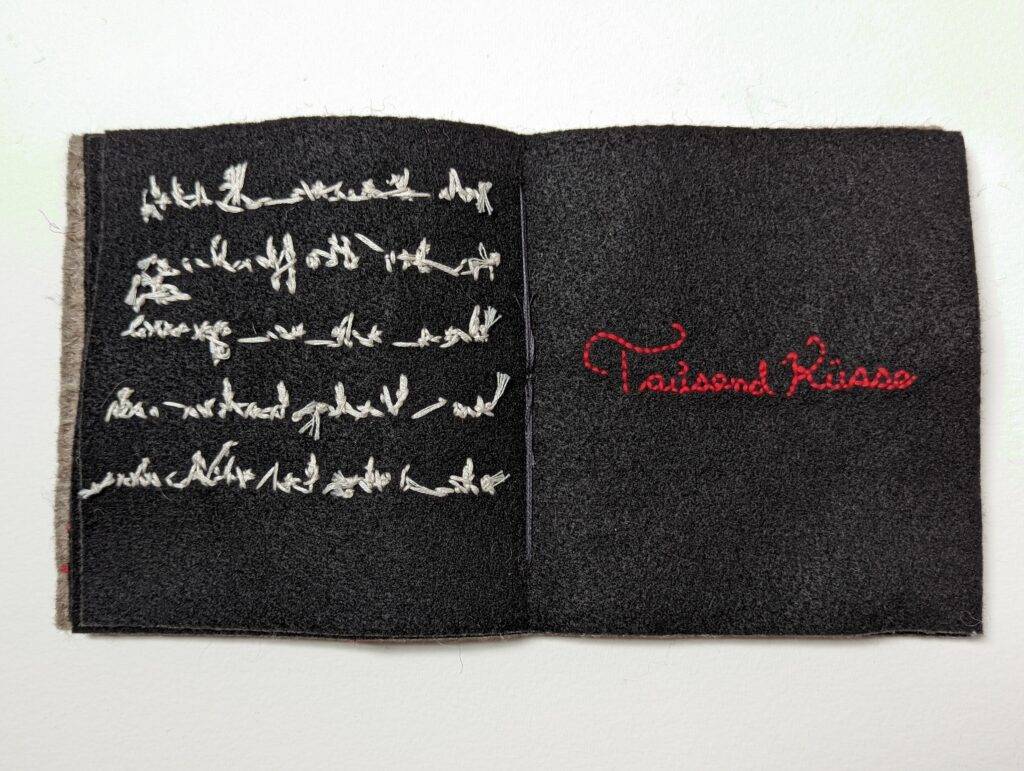

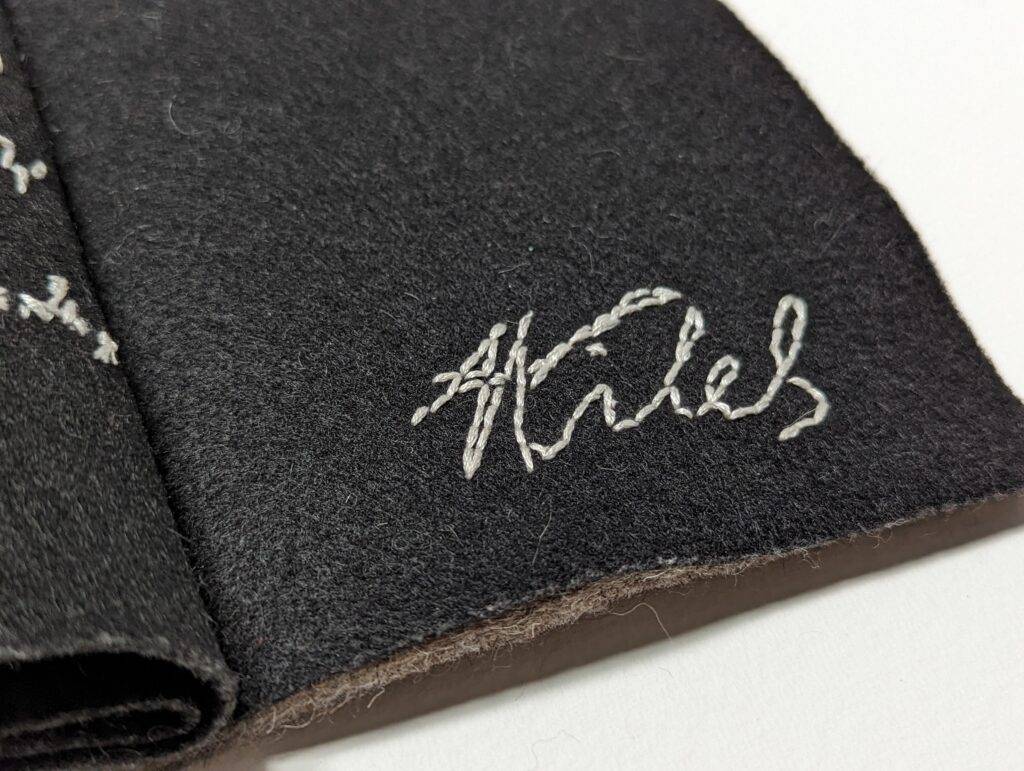

Last week, I completed my first piece for Memorial Gestures, an artist’s book in response to a letter written on the back of a photograph from Saul Erner’s father Hilel—it was the last photo Hilel sent to his family before he was murdered by the Nazis in 1942. I discovered this artefact thanks to Holocaust Centre North’s archivist, Hari, and was immediately struck by the phrase “Tausend Küsse,” which translates to “a thousand kisses” in English. (The field of tiny embroidered red x’s on the cover are a reference to this.) In order to create the artist’s book, I followed Hilel’s actual handwriting by using a printed copy of the letter as a guide while embroidering the felt pages. Embroidery is a slow and quiet process, and this manner of creation forced me to handle each letter of the handwriting with consideration and care—an act which caused me to feel more deeply the love that is inherent in his words.

There is a full video walkthrough and translations of the artist’s book on my Instagram, @laurafisherartiste. Feel free to give me a follow if you’re interested in following along with my research and artwork!

I am deeply grateful to Holocaust Centre North and the Iby Knill Bursary for sponsoring Memorial Gestures, and to the survivors who have enabled me to work with their stories. I have felt so warmly welcomed by all of the helpful, dedicated, and wonderful staff at Holocaust Centre North. The fact that I’m being invited to handle these histories carries an enormous gravity for me—I recognize the amount of care and dedication that goes into creating and caretaking for such a collection, and the level of trust involved in allowing artists to come interpret it. This responsibility grounds and bolsters the trauma-conscious focus that I bring to every aspect of this residency, and I am immensely honored to be a part of it.