As we approach the anniversary of the liberation of the Theresienstadt (or Terezin) ghetto on the 8th and 9th of May, we wanted to share the story of one of our most unique items in our archive: postcards from the ghetto.

Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt was unique within the Third Reich. Located north of Prague, then Czechoslovakia, it became operational on 24th November 1941 until its liberation. The ghetto served as a transit camp for Jewish people being deported to the killing sites in the East until October 1944, and also as a ghetto where prisoners were used as forced labour. Approximately 140,000 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt, of these nearly 90,000 were ‘sent to the East’ and 33,000 died within the ghetto itself from poor conditions, disease, forced labour and starvation.

Theresienstadt was an important instrument within the Nazi propaganda machine. It was chosen as the location to host a visit from the International Red Cross in June 1944, during which the ghetto was ‘beautified’ to deceive the visitors. To this end, the Nazis also shot a revealing documentary in 1944 for external audiences, which depicts the inmates in Theresienstadt working contentedly on nearby farms and participating in recreational activities.

Credit: USHMM

Postcards

Inmates in the Theresienstadt ghetto were allowed to receive packages and also send postcards to friends and relatives. The postcards had to be written in German and were heavily censored. Some people sent secret messages within their postcards to let the outside world know what was happening or to ask for assistance.

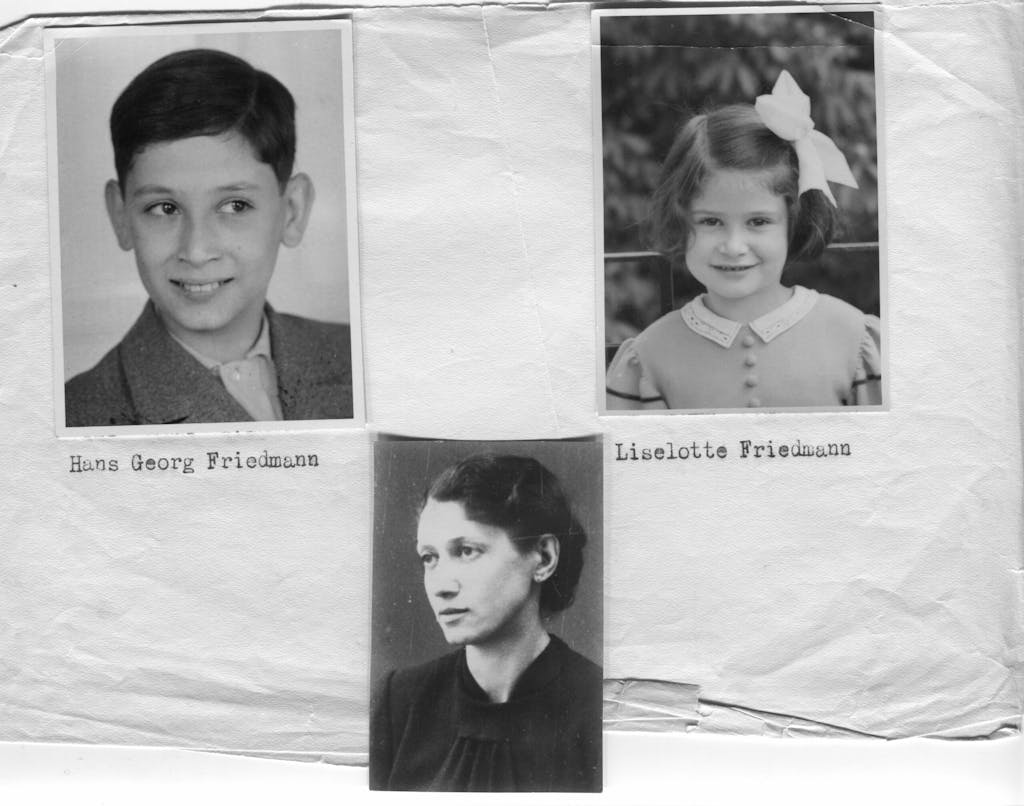

The postcards in our archive were mainly written by Hugo Friedmann to a family friend. Hugo, his wife Hilde, and their children, Hans Georg and Liselotte, were deported from Vienna to Theresienstadt on 9th October 1942. Some of the postcards are also written by Hilde.

In one postcard written by Hugo on 4th November 1943. He thanks his friend for a recent package of bread and toothbrushes and informs them that the family are well. He also gives an insight into life within the ghetto:

“I have much work in the local cultural life as a librarian and art historian with lectures and guidance, also [I] have much success as author of art historian poetry.”

These postcards not only reveal glimpses of life within the ghetto, but they also offer us insight into the bureaucracy of the Nazi regime. A formal receipt was issued for every postcard. The receipt below has been signed by Hugo, above the postage image showing Hitler’s image.

After Theresienstadt

The Friedmann family were deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz-Birkenau sometime in 1944. Hilde and Liselotte were killed in Auschwitz, and Hans Georg died in Dachau on 18th April 1945. Hugo was murdered in the Holocaust, the date of his death is recorded as 15th January 1945.

How did we receive these valuable and rare postcards within our archives? Tom Kubie, a nephew of Hilde, escaped Nazi persecution and came to Britain with his parents, siblings and maternal grandparents in 1939. While in Britain, Tom’s father was able to help move his sister, Else, and her son to safety. After the war ended Else returned to Vienna, Austria to retrieve surviving family possessions. The postcards were still with the family friend who had been the recipient of the wartime exchanges, and Else was able to retrieve them. They were then passed to Otto, Tom’s father. Along with the Friedmann family, over half of Tom’s family did not survive the Holocaust, including his paternal grandparents.

Hannah May Randall

30/03/21