Berta Klipstein

Berta was born and raised in a Jewish community in western Poland. When the war began, her family fled to the Soviet Union and were interned in a gulag.

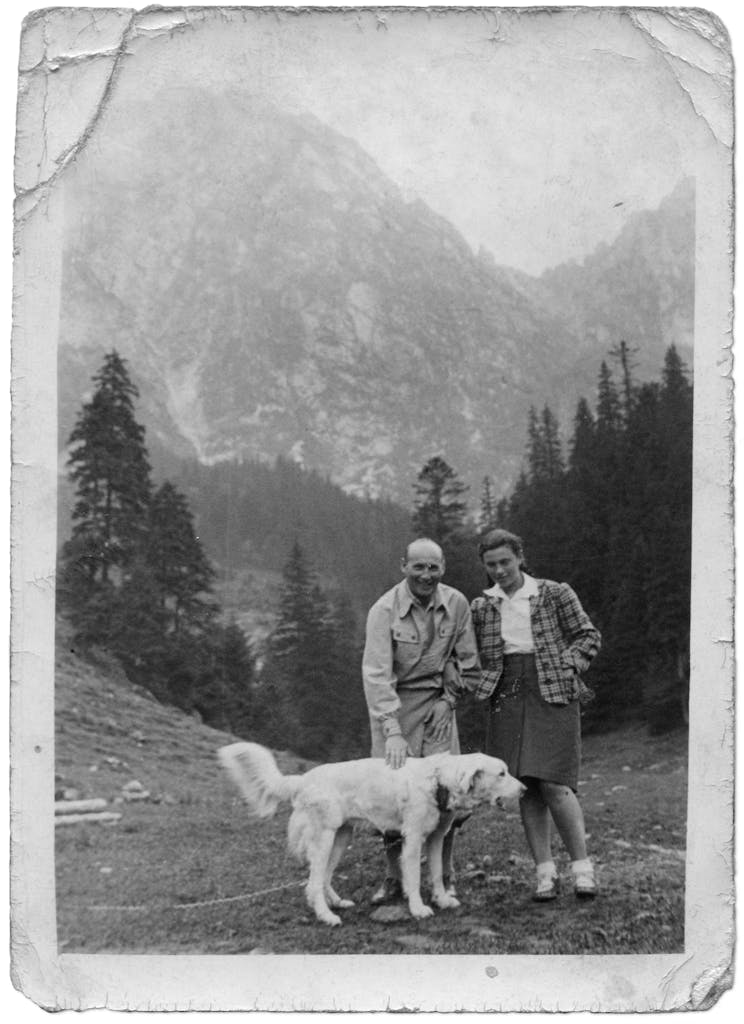

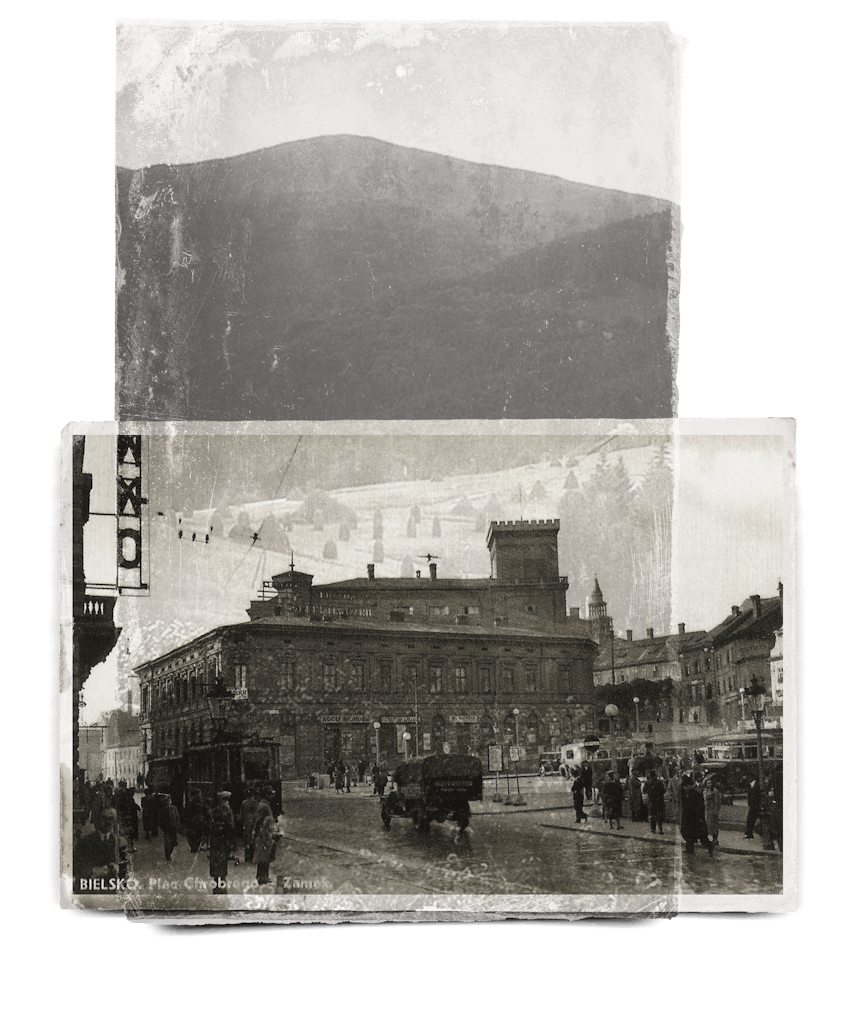

Berta was born in Bielsko (now called Bielsko-Biała) in southern Poland in March 1927. Berta grew up as an only child in a vibrant Jewish community and attended a Jewish school. She played the piano and performed in school concerts. Along with her parents, she often attended the theatre and cinema, and enjoyed long hikes in the nearby mountains. Berta’s father died of cancer in 1936, when she was 9 years old, and her mother remarried two years later.

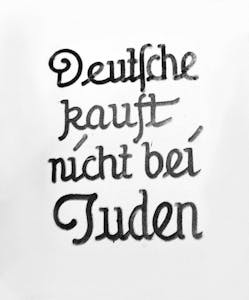

As support for the Nazis grew in the 1930s, antisemitism escalated throughout Poland. Berta remembers the German businesses in town hanging portraits of Adolf Hitler on their walls, while Jewish shops were boycotted, including Berta’s family’s optician business. Pickets stood outside saying: “Don’t buy from Jews.” Berta also remembered a pogrom. It seemed that war with Germany was inevitable.

On 1 September 1939, Berta was woken at 5.30am by the sound of German bombs. The German invasion of Poland had begun. The family spent the day hiding in the cellar with their neighbours. Once night fell, they returned to their home and had an evening meal. After some discussion, they made the difficult decision to flee and leave their home for the last time. Berta was just 12 years old:

“So we left her [our cleaner] with everything, took a big key to the front door of the apartment house, found ourselves in the street in real darkness because it was a real blackout, and we were refugees.”

The family fled the German advance towards the East, at first by train and then by horse-drawn cart, arriving in Soviet-occupied Łuck, where they spent nine months. The Soviet secret police pressured refugees, including Berta’s family, to take Soviet citizenship. When they refused, the family were rounded up and forced onto cattle wagons to the East. With minimal rations and no toilet facilities, the family spent two weeks on the wagons before arriving in Siberia.

The family were interned in a gulag, carrying out forced labour to fell trees in the forest to support the Soviet war effort. They were later moved to another gulag where Berta was allowed to attend primary school. She later lived with one of her teachers and worked for her as a housemaid, which meant she evaded doing hard physical labour. However, life was still difficult, as she was given little food and was forced to sleep in a cold corridor. Eventually, she had to return to the gulag, where she often fell ill with malaria:

“And we shall never know how many people were left there and did spend the rest of their natural life in those camps, because nothing is known.”

After Germany declared war on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviet Union joined the Allied forces and found itself on the same side as Poland in the war against Nazi Germany. As Polish internees of the gulags were no longer the enemy of the Soviets, Berta and her family were freed.

They left Siberia and travelled across Russia and Kazakhstan to a town called Kokand in Uzbekistan. They tried to make a new life there and Berta earned money knitting clothing and was even able to attend school once more. In 1943, Berta’s stepfather volunteered to join the new Polish army fighting alongside the Soviet Red Army and, after two years, was able to secure permission for the family to return home to Bielsko.

When they returned home to Poland, they discovered that antisemitism was still widespread. They also learned about the fates of their friends and family. Fearing further discrimination and persecution if they remained, Berta’s stepfather managed to obtain permission for Berta to leave. Alongside other young refugees, Berta joined Rabbi Dr Solomon Schonfield, who had been instrumental in organising the Kindertransport evacuations in the 1930s, to emigrate to London.

Now aged 19 years old, Berta lived with her aunt and won a free place at college to study chemistry – she was the only female student in the college. She went on to work at Tate & Lyle and earned a degree from London University.

After gaining British citizenship in 1951, Berta was contacted by her Polish boyfriend Zygi, who had escaped to Italy with his mother. Berta reunited with him in Italy and eventually he managed to come to England, where they were married.

They made a new life in Bradford. Zygi worked in a weaving firm, becoming its head designer for 28 years while Berta became a freelance translator, working until her seventies. Berta continued to pursue her hobby of knitting and designing clothes for herself, and also worked as a knitwear pattern designer. They also had three children.

After her husband died in 2014, Berta emigrated to Israel to be closer to her family. Berta sadly passed away in July 2023 and is missed by all who knew her.

Can you help us?

Without the work of charities like ours, stories like Berta Klipstein's will be lost and forgotten. Please donate generously to ensure that Berta's story can a force for good in the modern world.

- £